The Battle of Albert commenced and was part of the Second Battle of the Somme, with the British Third Army fighting over the old battlegrounds of 1916. The battle was a success pushing the German 2nd Army back over a 34 mile front, with Albert being re-taken on the 22nd August. Bapaume fell a week later on the 29th August 1918.

Category: Uncategorized

18th Aug 1918: 22nd Bn suffer two-thirds casualties in hopeless Herleville attack

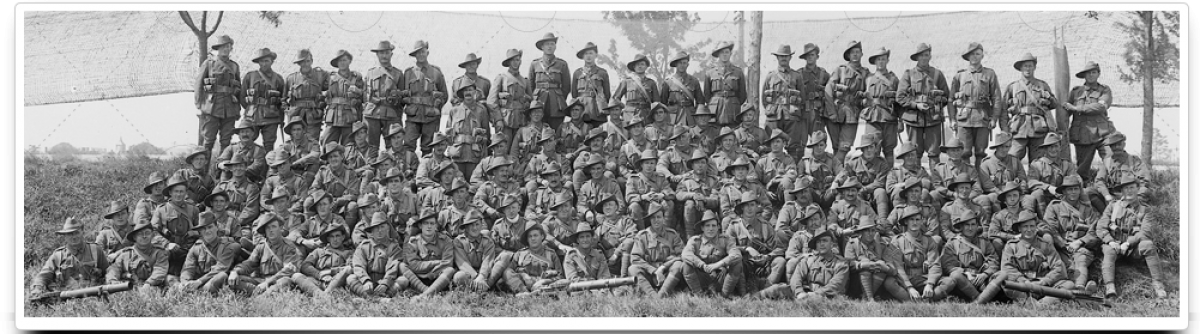

The woefully under-strength Australian 6th Brigade attack at Herleville, with the three companies of the 22nd Battalion, B on the left, A in the centre and D on the right, was met by heavy artillery and machine gun fire from the outset. Despite this D Company captured their objective. Advancing over open country D Company lost twelve men of its original thirty before reaching it, with the survivors holding on until assistance arrived later in the morning. D Company commanding officer, Lieut. McCartin, MC, (photograph right) was twice wounded in the attack but continued to the objective. When he found the crucifix on his left still strongly held by the enemy he made his way across the open and past the strong-point to the headquarters of the support C Company where he was again seriously wounded in the face as communication was made with Lt-Col. Wiltshire’s Battalion HQ. McCartin was told to return to the rear, but instead he attempted to return to his men whereupon he was killed by a shell. McCartin, initially a Private and one of the original Anzac men, was one of the most popular officers and held in high regard by all that he came in contact with.

The woefully under-strength Australian 6th Brigade attack at Herleville, with the three companies of the 22nd Battalion, B on the left, A in the centre and D on the right, was met by heavy artillery and machine gun fire from the outset. Despite this D Company captured their objective. Advancing over open country D Company lost twelve men of its original thirty before reaching it, with the survivors holding on until assistance arrived later in the morning. D Company commanding officer, Lieut. McCartin, MC, (photograph right) was twice wounded in the attack but continued to the objective. When he found the crucifix on his left still strongly held by the enemy he made his way across the open and past the strong-point to the headquarters of the support C Company where he was again seriously wounded in the face as communication was made with Lt-Col. Wiltshire’s Battalion HQ. McCartin was told to return to the rear, but instead he attempted to return to his men whereupon he was killed by a shell. McCartin, initially a Private and one of the original Anzac men, was one of the most popular officers and held in high regard by all that he came in contact with.

A Company in the centre had been faring badly. They were only twenty-four in all, in five small sections, at about seventy yards interval when they commenced a bombing fight with the Germans in the trench beyond. Lieut.’s Fulton and Evans were both wounded and command fell to Lieut. Smith, MM. It was not until ten of the twenty-four had been killed or wounded and no more bombs were left that the impossible was abandoned and the little party withdrew to a communication trench by the crucifix. Amongst those killed from this company was Sgt Ellis (photograph right) who set a magnificent example to his men urging them on, throwing bombs and fighting desperately until he was killed. Lieut. Woods of the 7th Machine Gun Company rushed forward to help A Company that he was attached to, establishing his gun in full view of the enemy and did wonders working his gun until a bomb landed too close and in the attempt to throw it back it exploded inflicting wounds that he would succumb to back at the Casualty Clearing Station.

A Company in the centre had been faring badly. They were only twenty-four in all, in five small sections, at about seventy yards interval when they commenced a bombing fight with the Germans in the trench beyond. Lieut.’s Fulton and Evans were both wounded and command fell to Lieut. Smith, MM. It was not until ten of the twenty-four had been killed or wounded and no more bombs were left that the impossible was abandoned and the little party withdrew to a communication trench by the crucifix. Amongst those killed from this company was Sgt Ellis (photograph right) who set a magnificent example to his men urging them on, throwing bombs and fighting desperately until he was killed. Lieut. Woods of the 7th Machine Gun Company rushed forward to help A Company that he was attached to, establishing his gun in full view of the enemy and did wonders working his gun until a bomb landed too close and in the attempt to throw it back it exploded inflicting wounds that he would succumb to back at the Casualty Clearing Station.

On the extreme left B Company suffered severely. Under the command of Lieut. Westaway the thirty-three men set off under heavy artillery and machine gun fire, suffering many casualties before reaching their objective. The survivors joined forces in a large shell hole within fifty yards of the enemy and opened fire with a Lewis gun and rifle grenades. The gun was soon knocked out of action by a bomb and the grenades expended. Sgt Bregenzer, DCM, (photograph right) jumped into the open calling for the Germans to surrender but he was killed immediately. Neither the flares nor the SOS signal sent up for artillery support were responded to and the enemy worked closer firing a machine gun and grenades into the now defenceless garrison of the shell-hole. Lieut. Westaway and several men were killed and most of the rest wounded before being surrounded and taken prisoner. [Read the letters and notes from Lieut. Mallinson on his account in the shell hole, being taken prisoner, and the exchange of letters between Mallinson and Lieut-Col. Wiltshire on the futility of the attack].

On the extreme left B Company suffered severely. Under the command of Lieut. Westaway the thirty-three men set off under heavy artillery and machine gun fire, suffering many casualties before reaching their objective. The survivors joined forces in a large shell hole within fifty yards of the enemy and opened fire with a Lewis gun and rifle grenades. The gun was soon knocked out of action by a bomb and the grenades expended. Sgt Bregenzer, DCM, (photograph right) jumped into the open calling for the Germans to surrender but he was killed immediately. Neither the flares nor the SOS signal sent up for artillery support were responded to and the enemy worked closer firing a machine gun and grenades into the now defenceless garrison of the shell-hole. Lieut. Westaway and several men were killed and most of the rest wounded before being surrounded and taken prisoner. [Read the letters and notes from Lieut. Mallinson on his account in the shell hole, being taken prisoner, and the exchange of letters between Mallinson and Lieut-Col. Wiltshire on the futility of the attack].

The task set for the men that day was a hopeless cause, and many a brave man gallantly lost their lives. Of the ninety men who took part in the attack, nineteen were killed, and a further forty-one wounded, or taken prisoner. Fifteen men from the Battalion were awarded for their bravery that day. With the British 32nd Division within Monash’s Corps replacing the 2nd Division that evening, all that was left of the 22nd Battalion, some seventy fighting men in all, were relieved by the 2nd Battalion of the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, some 670 strong. When the 22nd Battalion came out of the line, there were only nine members of B Company.

17th Aug 1918: Orders issued to depleted 6th Bgde to attack Herleville at dawn

Through the efforts of the previous nights the line had been pushed up to within four hundred yards of strong German posts on the outskirts of the village of Herleville. These were garrisoned, as later found out, by a portion of a Guards Division specially brought from reserve with instructions to stay at all costs and repel any attack that might be attempted. They were supported by strongly reinforced artillery which was always active, and its fire rising frequently to barrage intensity.

The 24th, 22nd and 23rd Battalions held the 6th Brigade frontage from left to right, with the road leading to Herleville running between the 24th and 22nd Battalions. About four hundred yards in front of the 22nd Battalion was a crucifix, joined to the village by a sunken road and traversed in places by trenches and bordered on the far side by a high bank which served as a parapet for a strongly held trench. Around the crucifix itself there was a simple trench system. Orders were received to attack on the following morning at 4.15am.

The 24th, 22nd and 23rd Battalions held the 6th Brigade frontage from left to right, with the road leading to Herleville running between the 24th and 22nd Battalions. About four hundred yards in front of the 22nd Battalion was a crucifix, joined to the village by a sunken road and traversed in places by trenches and bordered on the far side by a high bank which served as a parapet for a strongly held trench. Around the crucifix itself there was a simple trench system. Orders were received to attack on the following morning at 4.15am.

So depleted was the Battalion’s fighting strength that they could muster only 90 bayonets across three Companies for the attack, far too few to cover the ½ mile frontage allotted to them and for ground that had no particular value. These facts were most strongly represented but orders were nevertheless issued that the attack would take place. Wave formations were impracticable and thin section groups were formed for the attack. Owing to the limited artillery available the barrage was arranged in lanes only on selected places.

14th Aug 1918: Australians revert back to ‘peaceful penetration’ tactics

Following the cessation of the major Somme offensive on 11th August, the next week was dominated by local operations conducted by the front line units to straighten the front and to dispose of a number of strong points, small woods and village ruins which as long as they remained in enemy hands were a source of annoyance. The attitude of the Germans was alert but not aggressive, and that he showed every desire to stand and fight. There was no indication of any intention to withdraw out of the great bend in the river, a point corroborated from the statements from the steady toll of prisoners being taken.

11th Aug 1918: After four days Rawlinson’s 4th Army starts to meet stiffer resistance

Foch having been impressed by the progress so far and the success of the French to the south urged a continuation. Field Marshal Haig continued to press the general attack with General Rawlinson’s 4th Army on this the fourth day of the offensive, however he was now having doubts as he expected German reserves to be soon impeding progress here as the attacking forces came across the old trench lines and wire entanglements of the French sector in 1916. As a result his thoughts were now turning to his Third and Fourth Armies further north. The Australian role on the 11th August was for the 1st Division to continue swinging up the flank for the Canadians on the right at Lihons, while the 2nd Division on their left was to straighten the line and complete the objectives of the previous day. The 6th Brigade took over part of the firing line with the 22nd Battalion relieving portions of the 19th & 28th Battalions. Battalion Headquarters was positioned in an old German dug-out in the ravine to the east of the village of Framerville, which contained many interesting German documents left behind.

8th Aug 1918: ‘The Black Day of the German Army’ in the Great War

The great Amiens 1918 offensive saw the Allied forces on the Western Front make the decisive breakthrough that would ultimately lead to the German surrender and the signing of the Armistice 100 days later. Spearheaded by the Australian and Canadian forces in the centre and supported by the British and French on both flanks, the success on what General Ludendorff would call ‘the Black Day of the German Army’ was put down to secrecy & planning, integration between all the various fighting and support units, the fighting spirit of the attackers, tanks, plus a little bit of luck with the early morning mist that helped to conceal the early stages of the advance. The German Army lost 30,000 men that day, about half having surrendered, and never recovered from this point.

The great Amiens 1918 offensive saw the Allied forces on the Western Front make the decisive breakthrough that would ultimately lead to the German surrender and the signing of the Armistice 100 days later. Spearheaded by the Australian and Canadian forces in the centre and supported by the British and French on both flanks, the success on what General Ludendorff would call ‘the Black Day of the German Army’ was put down to secrecy & planning, integration between all the various fighting and support units, the fighting spirit of the attackers, tanks, plus a little bit of luck with the early morning mist that helped to conceal the early stages of the advance. The German Army lost 30,000 men that day, about half having surrendered, and never recovered from this point.

7th Aug 1918: Lt-Gen Monash addresses his troops

To The Soldiers of The Australian Army Corps

To The Soldiers of The Australian Army Corps

For the first time in the history of this Corps, all five Australian Divisions will tomorrow engage in the largest and most important battle operation ever undertaken by the Corps. They will be supported by an exceptionally powerful Artillery, and by Tanks and Aeroplanes on a scale never previously attempted. The full resources of our sister Dominion, the Canadian Corps, will operate on our right, while two British Divisions will guard our left flank. The many successful offensives which the Brigades and Battalions of this Corps have so brilliantly executed during the past four months have been the prelude to, and the preparation for, this greatest culminating effort. Because of the completeness of our plans and dispositions, of the magnitude of the operations, of the number of troops employed, and of the depth to which we intend to over-run the enemy’s positions, this battle will be one of the most memorable of the whole war; and there can be no doubt that, by capturing our objectives, we shall inflict blows upon the enemy which will make him stagger, and will bring the end appreciably nearer. I entertain no sort of doubt that every Australian soldier will worthily rise to so great an occasion, and that every man, imbued with the spirit of victory, will, in spite of every difficulty that may confront him, be animated by no other resolve than grim determination to see through to a clean finish, whatever his task may be. The work to be done tomorrow will perhaps make heavy demands upon your endurance and the staying powers of many of you; but I am confident, in spite of excitement, fatigue, and physical strain, every man will carry on to the utmost of his powers until his goal is won; for the sake of AUSTRALIA, the Empire and our cause. I earnestly wish every soldier of the Corps the best of good fortune, and glorious and decisive victory, the story of which will echo throughout the world, and will live forever in the history of our homeland.

JOHN MONASH

Lieut.-General

Commander Australian Corps

6th Aug 1918: German raids raise anxiety ahead of the great offensive

A German raid on an outpost of the 51st Battalion in the 13th Brigade resulted in five men being taken prisoner in an area previously held be the French, thus raising concerns amongst the senior commanders that the Germans might become suspicious or extract information from the prisoners and so go on a state of heightened alert. Captured German reports later showed that despite intensive questioning the Australian prisoners did not divulge anything beyond their name and unit, and it went further by praising these men and holding them as a model on how their own soldiers should react. As a result of the raid it was decided that the Canadians could not relieve the 13th Brigade until the very last minute, therefore depriving General Maclagan of one of his brigades, so Monash took the decision to temporarily transfer one of the AIF 1st Division brigades which was due to arrive in the coming days. Later that night the 1st Brigade having been hastily despatched, arrived for their involvement in the forthcoming operation. To the north of the river Somme a German counter-attack retook the ground taken a week previously by the 8th Brigade and now held by Butler’s III Corps, taking 8 officers and 274 other ranks prisoner. There was no sign that the Germans discovered anything new, but for Monash this vulnerability of his left flank across the river was evident and causing great concern.

4th Aug 1918: Gen. Plumer delivers highest praise to AIF 1st Div as they head south

During a small memorial service held on the fourth anniversary of the beginning of the war, the commander of the British 2nd Army Sir Herbert Plumer asked Major-General Glasgow to bring some of his senior officers and then spoke to them: ”You are leaving my army. I am sorry that I cannot inform you where you are going or what you are about to do. I am sorry to lose you, but I wish you success. You know, gentlemen, that it is not my practice to make eulogistic speeches – there will be plenty of time for that after the war. At the same time I would like to tell you that there is no division, certainly in my army, perhaps the whole of the British Army, which has done more to destroy the morale of the enemy than the 1st Australian Division.”

3rd Aug 1918: HS Warilda sunk with loss of 123 lives

Following the conversion to a hospital ship, HS Warilda spent a few months stationed in the Mediterranean, before being put to work transporting patients across the English Channel. Between late 1916 and August 1918 she made over 180 trips from Le Havre to Southampton,carrying approximately 80,000 patients. In February 1918 HS Warilda was struck by a torpedo which fortunately failed to explode, and the following month collided with another ship the SS Petit Gaudet off the Isle of Wight, the latter being seriously damaged. However worse was to befall her when on 3rd August 1918 when transporting wounded soldiers from Le Havre to Southampton she was torpedoed by the German submarine UC-49 despite the clear display of the Red Cross markings. Damage to the engine room meant she sailed around in a circle at 15 knots, and the lifeboats could not be launched until the steam ran out. One of her escorts attempted a tow, but the line had to be cut and she sank in about two hours. That night the HS Warilda had 801 persons on board with 471 invalids, including 439 cot cases. 123 people lost their lives, including all the engine room staff, all the occupants of “I” ward (the lowest ward containing 101 “walking” patients), and 19 people from capsized lifeboats. Amongst those that died were fifteen Australians and the Deputy Chief Controller of the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corp, Mrs Violet Long (photograph left).

Cross markings. Damage to the engine room meant she sailed around in a circle at 15 knots, and the lifeboats could not be launched until the steam ran out. One of her escorts attempted a tow, but the line had to be cut and she sank in about two hours. That night the HS Warilda had 801 persons on board with 471 invalids, including 439 cot cases. 123 people lost their lives, including all the engine room staff, all the occupants of “I” ward (the lowest ward containing 101 “walking” patients), and 19 people from capsized lifeboats. Amongst those that died were fifteen Australians and the Deputy Chief Controller of the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corp, Mrs Violet Long (photograph left).