A case study investigating the discipline record of the Australian soldiers during the First World War combining published literature with the service records of the 5th Reinforcements 22nd Battalion [Second and updated version, following presentation to the Surrey branch of the Western Front Association, 21st July 2021]

A case study investigating the discipline record of the Australian soldiers during the First World War combining published literature with the service records of the 5th Reinforcements 22nd Battalion [Second and updated version, following presentation to the Surrey branch of the Western Front Association, 21st July 2021]

The discipline record of the Australian Imperial Force was the worst of the countries that fought within the British Army during the First World War. This case study examines the underlying reasons why this occurred and draws from the commentary and observations provided by C.E.W. Bean in his Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918 together with findings from other published literature. As part of the research in the ‘Following the Twenty-Second’ WW1 commemorative project, the service records of the 154 infantrymen of the Victorian based 5th Reinforcements 22nd Battalion are used to illustrate these observations. How representative of the AIF are the men from the 5th/22nd for this case study? They are comprised of men that enlisted in the great recruitment campaign of 1915, saw action throughout the time that the Australians were fighting on the Western Front, and in total they accounted for thirty Courts Martial with one man in seven being charged and sentenced, twice the rate of the AIF as a whole.

Military discipline is primarily a means to an end, that is to provide an effective fighting force that will achieve its military objectives. This case study explores whether the poor discipline of the Australian soldier was or was not detrimental to its effectiveness as a fighting unit.

Factors contributing to poor discipline in the AIF

The underlying cause for the poor disciplinary record of the AIF has its roots in four key areas: i) the character and personality of the man defined by the environment in which he was brought up; ii) the selective choice and use of punishments by the AIF as provided within the British Army Act; iii) paid six times more than the British soldier and being remote from home; iv) battle fatigue and strain particularly towards the end of the war in 1918.

i) Character & personality of the Australian soldier. Being brought up and living in a new country forged by a people not riven with class deference and where can-do frontier attitude was to the fore, the character of the Australian soldier was markedly different from soldiers from many other countries, notably the British ‘Tommy’ that he fought alongside. Volunteers to a man, the motivation for the Australian soldier lay within the character and environment that he had grown up with: not giving way when his mates were relying on his firmness; not having another unit do their unfinished work; fear of being haunted in later life that he lacked the grit to carry it through. As Charles Bean describes, ‘he was quick to act on his own initiative and as a result others instinctively looked up to the Australian private as a leader, sometimes to good, sometimes to bad’. He also saw himself as a civilian that had come to do a job, and not as a regular soldier that was more used to parade ground rigours and rules. Such men could not be easily controlled by the traditional discipline methods used in most armies, however they were seriously intent upon learning and readily controlled by anyone that showed real competence.

An example of this Australian character of being quick to act on his own initiative can be seen within our case study group while training in the Egyptian desert. In January 1916 and as the 5th/22nd were being transported in open carriages to be Taken on Strength into the 22nd Battalion an incident on the train occurred, and acting on initiative and what they believed was in good faith 2502 Pte Sharples (photograph right) along with 2185 Pte Morgan took it upon themselves to uncouple the carriages in order to bring the train safely to a halt. This however was misguided and potentially a very dangerous act, and as a result they faced a subsequent Field General Court Martial. Pleading not guilty, they were found guilty of ‘an act to the prejudice of good order and military discipline’ and sentenced to one year Imprisonment with Hard Labour. Approaching the end of his sentence back in Australia, Pte Sharples wrote a request to re-enlist, as he stated his pending discharge branded him as a ‘bad character’ which he saw as a life sentence. Pte Sharples requested in his letter for an opportunity to ‘faithfully serve my King and Country and earn for myself a clean and honourable discharge’. On 12thJanuary 1917 it was approved and Pte Sharples was released two weeks later, re-joining as 3470 Cpl Sharples of the 57th Battalion. Fighting with his new unit through 1918 Cpl Sharples was wounded just days before the AIF were withdrawn from the front-line. Although very much aware of the dangers facing him – he had two brothers serving in France, both of whom at that time had been wounded, and with 7367 Pte Sharples later being killed in action in April 1918 – and probably feeling a sense of injustice from the Army, for Cpl Sharples the motivational needs of honour, ‘doing one’s bit’, and not relying upon others to do his work was much greater.

An example of this Australian character of being quick to act on his own initiative can be seen within our case study group while training in the Egyptian desert. In January 1916 and as the 5th/22nd were being transported in open carriages to be Taken on Strength into the 22nd Battalion an incident on the train occurred, and acting on initiative and what they believed was in good faith 2502 Pte Sharples (photograph right) along with 2185 Pte Morgan took it upon themselves to uncouple the carriages in order to bring the train safely to a halt. This however was misguided and potentially a very dangerous act, and as a result they faced a subsequent Field General Court Martial. Pleading not guilty, they were found guilty of ‘an act to the prejudice of good order and military discipline’ and sentenced to one year Imprisonment with Hard Labour. Approaching the end of his sentence back in Australia, Pte Sharples wrote a request to re-enlist, as he stated his pending discharge branded him as a ‘bad character’ which he saw as a life sentence. Pte Sharples requested in his letter for an opportunity to ‘faithfully serve my King and Country and earn for myself a clean and honourable discharge’. On 12thJanuary 1917 it was approved and Pte Sharples was released two weeks later, re-joining as 3470 Cpl Sharples of the 57th Battalion. Fighting with his new unit through 1918 Cpl Sharples was wounded just days before the AIF were withdrawn from the front-line. Although very much aware of the dangers facing him – he had two brothers serving in France, both of whom at that time had been wounded, and with 7367 Pte Sharples later being killed in action in April 1918 – and probably feeling a sense of injustice from the Army, for Cpl Sharples the motivational needs of honour, ‘doing one’s bit’, and not relying upon others to do his work was much greater.

ii) Selective choice and use of punishments by the AIF. Military discipline in the British Army was dictated by the Army Act which gave a range of punishments covering the very wide spectrum of offences that could occur. Serious matters were tried by Field General Courts Martial, moderately serious by District Courts Martial, and small scale violations such as being late on parade, not saluting, dirty equipment etc. dealt with by the Officers and NCO’s of the man’s own unit. The ultimate penalty was the Death Penalty with the risk of being shot for a variety of reasons, but mainly for desertion, murder, and cowardice in front of the enemy. During the First World War 346 men of the British Army were executed, though 3,080 had been sentenced to death and with the majority having their sentence reduced. After the death penalty came a variety of sentences of incarceration through Detention, Penal Servitude or Imprisonment with Hard Labour, with the convicted placed either in a military compound or sometimes a prison. Field Punishments were also available, and as the name suggests carried out close to or in front of the man’s unit. Field Punishment Number 1 consisted of the convicted man being shackled in irons and secured to a fixed object, such as a gun wheel or post, and frequently in a crucifixion stance. Field Punishment Number 2 was similar except the shackled man was not fixed to anything.

Thus the Australian Imperial Force in WWI had a variety of punishments at its disposal, but driven by their own Parliament, public opinion, and the wishes of their own commanders were selective in which to use to maintain discipline within their force. As a consequence of a British run Court Martial and subsequent execution of two Australian officers Lieutenants ‘Breaker’ Morant and Handcock during the South African Boer War in 1902, the Australian Parliament introduced Section 98 of the Commonwealth Defence Act 1903, where no member of the Defence Force shall be sentenced to death by any court martial except for four offences: mutiny; desertion to the enemy; traitorously delivering up to the enemy any garrison, fortress, post, guard, or ship, vessel, or boat, or aircraft; and traitorous correspondence with the enemy.

During WWI 129 Australian soldiers were indeed given the death penalty sentence, 119 for desertion of which 117 of these cases were in France, but none of these sentences were carried through, for fear of the negative effect that it might have on this completely volunteer army and the support of the public at home. Appeals were made, particularly with the increase in desertions within the AIF in 1917, not just by the British High Command including Field Marshall Haig and General Rawlinson but also by General Birdwood – Anzac Commanding Officer Gallipoli to May 1918 – to carry out the death sentence on a few of the worst offenders in order to make examples and try to stop this worrying deterioration in discipline, but the Australian Parliament held firm in its belief.

Without the ultimate deterrent and faced with the growing problems of drinking and desertion while the AIF was in Egypt in 1915, Major-General Bridges adopted another approach by returning the worst troublemakers to Australia and asked Bean to publish a letter in Australian newspapers explaining the reasons. This act of humiliation came as a shock to the public at home and was resented by much of the force, but remained the most feared of punishments by the soldiers of the AIF until after Pozieres in August 1916. From this point its questionable effectiveness plus potential detrimental effect to the morale and the fighting spirit of the men and to the recruitment campaign, meant that this option of punishment was withdrawn. In a similar fashion, the use of Field Punishment Number 1 was also not widely used by Australian commanding officers, again as it was seen to be too much of a humiliation – cases were recorded where some men risked their own punishment by freeing the prisoner from the shackles. This type of punishment was also contrary to the attitudes displayed by some of the best officers in the Australian units, i.e. the officers that had the respect of their men by showing a sense of empathy and well-being for the men under their command.

The severest options for punishment were thus reduced, meaning that pretty much the worst that could happen to the Australian soldier would be to be locked away in a prison such as the Lewes Detention Centre (photograph above) for the duration of the war with the prospect of release at the end of the hostilities, and even though the regimes were harsh were still not as bad as being out on the front-line. For the same reasons that some senior officers advocated the carrying through of the death penalty to act as a deterrent, Lieutenant-General Godley of the New Zealand Division and then II Anzac Corps recommended that soldiers receiving custodial sentences should at least expect that these will remain in place even after hostilities had finished, but again this was rejected. Indeed, of the 22 custodial sentences given to the 5th/22nd, six were either commuted or suspended during the war thereby releasing the charged man back to his unit. The most unfortunate of these was 2381 Pte Smillie who received 18 months Imprisonment with Hard Labour in May 1918 for disobeying an order while recovering from sickness in hospital in Le Havre. Up until this point Pte Smillie had been one of the few in the 5th/22nd ever present with the battalion and had come through Pozieres, Bullecourt and 3rd Ypres unscathed, along with a clean discipline record. Pte Smillie was released from prison a month into his sentence but when back with the battalion became a casualty from one of the many German gas bombardments that occurred in July and sadly died five days later from the terrible effects of the gas.

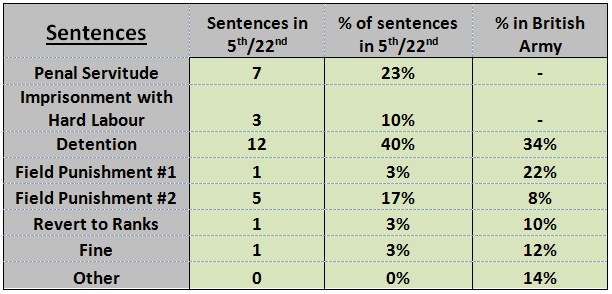

The more lenient and less humiliating approach taken by the AIF in its passing of sentences is reflected in the punishments given in the thirty cases of Courts Martial for the men of the 5th/22nd as shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Comparison of sentences between the 5th/22nd and British Army

The largest category for both the British Army and the 5th/22nd was Detention with 34% and 40% of sentences respectively, however to the 5th/22nd number are added 23% Penal Servitude and 10% Imprisonment whereas for the British these other two forms of incarceration are small and included just within ‘Other’ forms of sentence. Included in these cases for the 5th/22nd are 2487 Pte Payne who, in his second Court Martial, is just one of 143 in the entire British Army who received a life Penal Servitude sentence during the war, and 2486 Pte Barton who, in his fourth Court Martial, was one of just 461 to receive a Penal Servitude sentence of 15 years having deserted with Pte Payne from the reserve line at Villers-Bretonneux. Ptes Payne and Barton had very similar indiscipline records and on two occasions absconded together. They were also both wounded in action at Pozieres in August 1916.

The differences in attitude to Field Punishment No.1 can also be seen with only one of the thirty 5th/22nd cases brought before a Court Martial resulting in this punishment against the 60,210, or one in every five cases within the British Army. This sentence was given to 2412 Pte Smith after his third court martial during the war, this time for drunkenness while at the AIF Depot in Le Havre during his journey back to the battalion after being wounded at Dernancourt in April 1918. Speculation is that FP No.1 was issued at the Field General Court Martial held at the AIF Depot and therefore away from his unit. Pte Smith was wounded in action on a total of three occasions, and was promoted to Lance-Corporal in October 1917 following Third Ypres.

iii) High pay and remoteness from home. The Australian soldier was known as the ‘six bob tourist’ on account of his relative high rates of pay versus the British Tommy, with 5 Shillings in the soldier’s pay book and 1 Shilling deferred until discharge. Soldiers could elect how much was allocated (or not!) back to Australia and their families. The result of this relative affluence was that men were more willing to go Absent Without Leave and accept the fine, plus have more money when they were out on the town for more alcohol and therefore drunkenness, and other distractions that might come by their way! The Rising Sun badge thus was a target for exploiters and as a consequence of their pay and remoteness from home the Australians had a Sexually Transmitted Disease rate of twice the British Army, similar to the other Dominion forces.

The graph right shows the higher rates of STD’s contracted by the Dominion forces compared to those in the British divisions over the duration of the war. With the Canadians paid a similar rate to the Australians, the impact of pay and distance from home is evident in this indiscipline metric. A Military Order in 1915 meant that infected soldiers in the AIF were deemed absent from duty and forfeited their pay and leave was stopped. Average STD treatment was 6 weeks and some in High Command saw this as akin to self harming and as a result should be dealt with more severely. It is estimated that there were 63,350 STD cases within the 417,000 men of the AIF – in our 5th/22nd case study group 18 men out of 154 within the 5th/22nd contracted an STD, with 26 cases in total. Why was STD contraction an issue? Within the 5th/22nd, after respiratory tract infections STD’s were the second highest cause of hospitalisation and hence absence from the unit throughout the war, plus cases were higher in 1918 when recruitment was down and casualties were rising (see graph below).

The graph right shows the higher rates of STD’s contracted by the Dominion forces compared to those in the British divisions over the duration of the war. With the Canadians paid a similar rate to the Australians, the impact of pay and distance from home is evident in this indiscipline metric. A Military Order in 1915 meant that infected soldiers in the AIF were deemed absent from duty and forfeited their pay and leave was stopped. Average STD treatment was 6 weeks and some in High Command saw this as akin to self harming and as a result should be dealt with more severely. It is estimated that there were 63,350 STD cases within the 417,000 men of the AIF – in our 5th/22nd case study group 18 men out of 154 within the 5th/22nd contracted an STD, with 26 cases in total. Why was STD contraction an issue? Within the 5th/22nd, after respiratory tract infections STD’s were the second highest cause of hospitalisation and hence absence from the unit throughout the war, plus cases were higher in 1918 when recruitment was down and casualties were rising (see graph below).

iv) Battle fatigue and strain in 1918. The five Australian divisions were in the front line from the end of March to October 1918. When the German Spring Offensive was unleashed upon the British on the Somme the Australians were quickly dispatched south from Flanders and through their determination and dogged defence helped halt the enemy advance in front of Amiens. During the relative lull on the British front in May to July, the Australians kept relentless and demoralising pressure on the German Army with their peaceful penetration stunts, and then following the successful Hamel attack in July, alongside the Canadians spearheaded the breakout at Amiens before pushing on towards the final Hindenburg Line defences. However the impression grew that Australian troops were being asked to do more than their fair share of the difficult fighting and picking up others unfinished work.

Battle attrition was now exerting a heavy toll and the flow of fresh recruits was drying up. Many battalions were now down to 150 men, manpower equivalent of just 3 full strength platoons in a Battalion of 16 platoons (example shown in photograph of understrength platoon from B Coy of the 29th Battalion 8th Aug 1918). On 31st August Mjr-Gen Hobbs warned Lt-Gen Monash that the stress on the Australian 5th Division was approaching limits of endurance, and on the 14th September having just been relieved, the 59th Battalion were told to follow the enemy’s retirement. Three platoons refused and their officers supported their action. The refusal was eventually overcome, but the point had been made in what Bean refers to as the first mutiny in the AIF.

On the 3rd September after Battle of Mont St. Quentin the strain on 2nd & 3rd Divisions was even greater – during this battle 8 VC’s were won, the most in any one engagement by the Australians. On the 21st September 119 men of one company in the 1st Battalion, having lost all their officers, refused to join another company and walked to the rear. The 1st Battalion attack was carried out by three companies totalling just 10 officers and 84 men; 118 men were found guilty of desertion, not mutiny. The following day due to the low number of men left the 19th, 21st, 25th, 37th, 42nd, 54th, and 60th Battalions were all selected to be disbanded. All but the 60th Bn refused (as a result of Brig-Gen ‘Pompey’ Elliott’s forceful personality), with the selected battalions extolling the virtue of esprit de corps. However they did not refuse to fight and to make the point the 25th Battalion requested the most difficult task in the next fight by the 7th Brigade. With a long overdue relief expected soon, Monash decided to postpone any disbanding until after the Hindenburg Line had been taken.

Discipline an ever present problem

From the time of their arrival in Egypt, the Australian soldier was becoming well known for heavy drinking, going absent without leave, but also there were the more serious attacks on local inhabitants and robbery, the most serious of which were the Wasser riots of April 1915 in which over 2,000 Anzac troops ran riot in this red light area of Cairo. Some commanding officers such as Lieutenant-Colonel Gellibrand of the Australian 12th Battalion (latterly of the 6th Brigade and then Australian 3rd Division) took a balanced view while in Egypt that by trusting in the character of his men, relatively minor offences such as overstaying leave by a couple of days would be dismissed save for the paying of a fine, which most of the men saw as an acceptable price for their time away. However, with reinforcements arriving from Australia in late 1915 along with the returning Gallipoli veterans the decision was taken to relocate the AIF to the middle of the desert at Tel-el-Kebir, strategically closer to the Suez Canal and the expected Turkish attack, but also lessening the temptations of Cairo.

During the reorganisation of the AIF in February and March 1916, a number of unit commanders used this as an opportunity to move the troublemakers out to another unit. As it turned out 1 in 3 of the men of the 5th/22nd that received a Court Martial had at one stage been transferred out to another unit compared with 1 in 5 overall for the 5th/22nd. How many would have been identified as troublemaker’s at the time of their transfer is unknown, though 2329 Pte Carmody and 2416 Pte Stevenson had already had instances of being absent without leave.

Concern was growing in the British GHQ that the arrival of the Australians on the Western Front could have a destabilising effect on the discipline of the British and other Dominion forces that they would be fighting alongside. With the Australian 1st and 2nd Divisions preparing to leave Egypt for France in March 1916, General Birdwood wrote to all men serving in the AIF reminding them of their responsibilities and not to damage the fine reputation that had been won above the cliffs of Anzac Cove. Furthermore, fearing riotous behaviour upon their arrival in France steps were taken to move the arriving troops from the ships in Marseille Harbour to the waiting trains during the night to lessen the chance of men absconding into the bars as they marched through the city. As it happened, after the 2nd and then 1st Divisions had passed through, General Birdwood was informed that no troops had caused less trouble. The same gratitude and admiration was afforded to General McCay as the 5th Division passed through a couple of months later.

Table 2: Comparison of Charges brought before a Courts Martial

While stationed in Europe, Australian cases brought before a Court Martial (see Table 3 below) were proportionately much higher than any other section of the British Army. Although the ‘larrikin’ behaviour of slovenly dress, not saluting an officer, and bad language, was an irritant to the British, it was the more serious cases of absent without leave and desertion that the British GHQ was becoming concerned with. As shown in Table 2 above the percentage of Courts Martial for being Absent Without Leave in the AIF was 58%, about twice as much as in the British Army. For the 5th/22nd when the four cases of desertion in France are added to the eighteen of AWL, the total percentage for absenteeism was almost three in four cases brought before the courts. It should be noted however that of the eighteen Courts Martial cases of AWL, fifteen occurred while the soldiers were in England, frequently absconding while they were recuperating from their wounds in the Command Depots or overstaying leave.

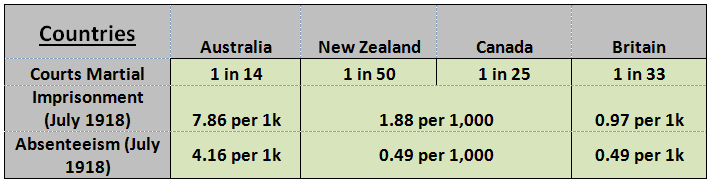

Although much was made of the Australian free-spirit, for British GHQ there appeared to be a strong correlation between discipline and punishment, as other dominion forces such as the Canadians and the New Zealanders which one could argue could have the same frontier type free spirit as the Australians and who too were thousands of miles away from home, had a much better disciplinary record. In 1915, before the arrival of the Anzacs on the Western Front, the Canadians were indeed regarded as second to none in terms of discipline, smartness and efficiency. A comparison between the numbers of Courts Martial between these countries is shown in Table 3 below, including comparative rates of absenteeism and the sentencing response by the courts.

Table 3: Country comparisons

As can be seen by the snapshot figure taken in July 1918 Australian soldiers were ten times more likely to go absent without leave than the New Zealanders or Canadians. When looking at their total time spent in the AIF, our case study group of the 5th/22nd shows that 44 men, i.e. more than 1 in 4 went absent at some time while in the army, with half of these being repeat offenders, the same proportion incidentally as the number that would face a Courts Martial for the offences of absent without leave or desertion. In all there were close to 100 instances amongst this group of going absent without leave, with a third of these occurring in 1917.

Given that both New Zealand and Canada employed the ultimate deterrent there appears to be a strong correlation between discipline and the use of the death penalty. As mentioned above requests were repeatedly made by British Army Commanding Officers such as General Rawlinson of the British 4th Army and then by Field Marshal Douglas Haig that examples should be made of certain bad cases and they should be shot, but each time the Australian Government refused. British GHQ was also exasperated that the Australian commanding officers were not making more use of Field Punishment No.1, particularly as it was viewed that a proportionately high number of Australians were living out the war in relative comfort in prisons. An example of its effectiveness was shown with the Australian 12th Brigade that was experiencing excessive numbers of Courts Martial for drunkenness, absence and refusing duty, and after the increased use of Field Punishment No.1 instances of the above declined significantly.

Although the rate of committing a military crime was very high for the Australian Army compared with other countries, it should be noted that a large majority of these occurred while the soldier was away from the firing line, either with his Unit recuperating or while on leave or in hospital or camp. Behaviour in camp or while on leave in England deteriorated in 1917 with the soldier’s time away from home lengthening leading to increased boredom and homesickness. While out of camp differences between the social conditions of the men and their host country including attitudes to women in the workplace rose to the surface creating tensions, fuelled by the six-times higher pay packet. Instances of Absent Without Leave were increasing, and with Army courts and authorities becoming bogged down with cases, officers were urged to use other means to avoid them. In September 1917 a memo from Australian 1st Division urged commanding officers to exercise discretion as to whether cases should be sent to Courts Martial, with the raising from seven days to 21 days of absence without leave before going to a Field General Courts Martial. This more tolerant approach, plus with the number of men in each unit falling due to the high number of casualties being inflicted, may explain why 2394 Pte Stephens and 2397 Pte Samways were not sent to FGCM despite being ‘illegal absentees’ for 41 days until apprehended while in England. Instead they were sent directly back to their unit in France.

Table 4: Distribution of Courts Martial through the AIF period on the Western Front

Table 4: Distribution of Courts Martial through the AIF period on the Western Front

The rate at which Australian soldiers were appearing in front of the military courts remained high throughout the war. Although AIF absolute numbers showed a decline in the six month periods in 1917 and 1918, Table 4 above also shows that the proportion of Australian soldiers that were sent for Courts Martial remained at about 1 in 14, on account of the declining numbers within the AIF as the war progressed. Moreover when you look at the instances of Desertion, i.e. one of the most serious offences, it can be seen in the graph above that the numbers increase as the war progressed on the Western Front, an indication that battle fatigue and strain was an issue. This fatigue factor can also be seen within the 5th/22nd (table 4 above) which shows an actual increase in Courts Martial in real terms in 1918, leading to a high proportion of 1 in 10 men still with the 22nd Battalion being sentenced during the first half of 1918. Of the four desertion cases of the 5th/22nd brought before the courts, one

The rate at which Australian soldiers were appearing in front of the military courts remained high throughout the war. Although AIF absolute numbers showed a decline in the six month periods in 1917 and 1918, Table 4 above also shows that the proportion of Australian soldiers that were sent for Courts Martial remained at about 1 in 14, on account of the declining numbers within the AIF as the war progressed. Moreover when you look at the instances of Desertion, i.e. one of the most serious offences, it can be seen in the graph above that the numbers increase as the war progressed on the Western Front, an indication that battle fatigue and strain was an issue. This fatigue factor can also be seen within the 5th/22nd (table 4 above) which shows an actual increase in Courts Martial in real terms in 1918, leading to a high proportion of 1 in 10 men still with the 22nd Battalion being sentenced during the first half of 1918. Of the four desertion cases of the 5th/22nd brought before the courts, one  occurred in the second half of 1917 when the 22nd Battalion was engaged in the Third Ypres campaign and the other three in the summer of 1918 while the Battalion was at Morlancourt and to the rear of Villers-Bretonneux. Another indicator of the decline in discipline as the war progressed, and particularly in 1918, are the instances of sexually transmitted diseases as highlighted in our cohort group in the second graph here on the right.

occurred in the second half of 1917 when the 22nd Battalion was engaged in the Third Ypres campaign and the other three in the summer of 1918 while the Battalion was at Morlancourt and to the rear of Villers-Bretonneux. Another indicator of the decline in discipline as the war progressed, and particularly in 1918, are the instances of sexually transmitted diseases as highlighted in our cohort group in the second graph here on the right.

The declining discipline in the AIF overall and as illustrated in our cohort group are likely to be a combination of factors: an indication of battle fatigue having endured more than two years facing the worst that the enemy and elements on the Somme and around Ypres could throw at them; the majority having been wounded and felt that ‘they had done their bit’; boredom and homesickness while recuperating away from the front in England. One such example was 2394 Pte Stephens (see below) who, having been wounded on four occasions – the most by any member of the 5th/22nd – and having received the Military Medal on the second from last day of fighting by the AIF in the war, went absent on Armistice Day, as in 1917 with his best mate 2397 Pte Samways. It is believed that in addition to ‘having done his bit’ Pte Stephens had another motive, as illustrated in his service records by the wedding certificate to his wartime sweetheart Minnie Taylor from Twickenham in May 1919.

Authorities had a difficult time all the way through to demobilisation in 1919 as the soldiers were becoming frustrated with the delays to their return to Australia. Included amongst the trouble makers during this time was 44 year-old 2494 Cpl Clack who in May 1916 had been transferred from the 22nd Battalion to AIF HQ and spent the entire war as escort to General Birdwood. Cpl Clack was found guilty at a Field General Court Martial of drunkenness while on active service in February 1919, and fined the princely sum of £1!

The character of a charged soldier in the AIF

Much has been attributed to the frontier-type spirit of the ‘bush’ in defining the Australian characteristic and behaviour. This would have only applied directly to about a quarter of the AIF soldiers as a whole, with the majority having been brought up in the towns and cities. However the can-do ethos or creed of the frontier miner or bushman in that you stick by your mate at all times became adopted by the majority of Australians regardless of where they were brought up. In our case study, the men of the 5th/22nd were all drawn from the centre and suburbs of Melbourne, and 11% from abroad, therefore exposure to the bush lifestyle and mentality would not have been directly relevant in defining their character, thus is more akin to an adoption of these characteristics.

A volunteer army will by its very nature contain a vast array of characters, all asked to put their lives at risk and carry out acts contrary to normal human behaviour. As a result it is inevitable that some hard cases and persons of bad character will enlist. Indeed the former, if managed properly, could be just the type of valued soldier that a unit would want, whereas those of bad character would need to be weeded out as they could become a source for demoralising within the unit. There is probably no better example of this than Pte John ‘Barney’ Hines (photograph above right). English born to German immigrant parents, Hines was married with two children but left for New Zealand where he developed a very bad criminal record. After a decade in New Zealand he moved to Australia where he enlisted into the AIF (stated he was 28 but much older) and joined the 45th Battalion. It is reported that during the Battle of Messines in June 1917 that he captured a force of 60 Germans by throwing Mills bombs into their pillbox, and was later wounded. According to a commanding officer, Hines was “a tower of strength to the battalion….while he was in the line“. Nicknamed the “Souvenir King“, Hines received nine Courts Martial for drunkenness, impeding military police, forging entries in his pay book and being absent without leave. As a result of these convictions, Hines lost several promotions he had earned for his acts of bravery. An officer from the 45th Battalion stated after the war that Hines had been “two pains in the neck”.

While the AIF was at Tel el Kabir, as Bean observed, it had become obvious that certain characters or criminals had enlisted, for example to run gambling schools or escape punishment in Australia, and for a tiny minority had no intention of reaching the firing line. For some men, the act of catching venereal disease while on leave or when absent without leave, was used as an effective way of keeping out of the front-line, a condition that many in GHQ placed akin to self-maiming.

Leading up to the Gallipoli landings and during their time in Egypt, Bean observed that many of the perpetrators of bad discipline in I Anzac appeared to be the older soldier and those born overseas. From our case study group there is no evidence that this carried forward to the period on the Western Front. For example the average age of the men of the 5th/22nd that were tried by Courts Martial was just over 25 years old compared with 26 years for the 5th/22nd as a whole, and 14% of these men were born overseas compared with 11% overall. Furthermore, investigation into the demographics of the 5th/22nd to see if there was a particular type of person from a certain profession pre-disposed to bad discipline, again showed that this was not a factor as seen in Table 5 below.

Table 5: Comparison of professions between with and without Courts Martial convictions

Within the case study group the small minority of bad characters identified by Bean does appear to be present, and the service records of two men from the 5th/22nd (not identified in this article) indicate very little intention of wanting to be in the firing line, not only from their repeat instances of going absent without leave, but during their time of absence they contracted on multiple occasions a sexually transmitted disease which would see them reside in hospital before absconding again and repeating the process. As indicated by this behaviour it soon became apparent to the authorities that being able to breakout of Bulford Hospital (1ADH) where most of the Australian Sexually Transmitted Disease cases were treated was pretty easy, so a new medical wing to treat STD cases was created at the Lewes Detention Centre (pictured above) in Sussex which also housed many of the men serving custodial sentences. This behaviour however was the exception rather than the rule and for the vast majority of the men that were brought before the courts they exhibited the attributes, experiences and character of the Unit as a whole.

Table 6: Comparison of character between soldiers with and without Courts Martial convictions

Table 6 above helps to demonstrate this showing that the percentage of men that faced Courts Martial had the same casualty rate (killed or wounded in action) as the rest of the 5th/22nd – including 2340 Pte Hosking and 2381 Pte Smillie being killed in action after having served their sentences. The proportion of men receiving an award for gallantry is also the same in both groups with 2335 Pte Hunt and 2347 Pte MacFarlane receiving the Distinguished Conduct Medal and 2394 Pte Stephens the Military Medal. Furthermore, despite absence from the front-line through their wounds, crime and subsequent detention, the period that the courts martial cohort spent with the Unit on active service was almost identical to that of the 5th/22nd as a whole at 44% and 45% respectively.

Let us look at the character of the three men from the 5th/22nd that received both a Court Martial and an award for gallantry in closer detail. Pte John ‘Jack / Darky’ McFarlane from Port Melbourne was an 18 year-old slaughterman when he enlisted in July 1915, and as a top sportsman including captain of the battalion football team, boxing champion and also swimming champion was a popular member of the 22nd Battalion. Pte McFarlane was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his conspicuous gallantry and daring while acting as a runner in both of the attacks at Broodseinde on the 4th and 9th October 1917. In May 1918 and while McFarlane was in Le Havre recovering from Trench Fever, an altercation in a bar led to him disobeying an order, striking an officer and resisting arrest. The subsequent Field General Court Martial found Pte McFarlane guilty and sentenced him to 3 years Penal Servitude along with the forfeiture of his DCM. Once the news of his sentence reached the battalion, good character statements from his commanding officers resulted in his sentence being reduced to one year and his DCM re-instated. His brush with authorities did not end there, as Pte McFarlane ended up in hospital after injuring himself falling from the top a fence while trying to escape prison, and while awaiting his return to Australia in July 1919 Pte McFarlane had enough of waiting for his allotted slot home so went walkabout in the UK before returning home in February 1921. After the war Jack ‘Darky’ McFarlane became a prominent member of the Port Melbourne Football Club becoming Club Secretary and to this day the club medal for Best and Fairest player of the year is named after him.

Like Pte McFarlane, Pte George Stephens (photograph left, standing) came from Port Melbourne and upon enlisting was learning a trade as a labourer with Taylor Pipe Works. His service record states an age of 18, but when Pte Stephens enlisted in July 1915 he was only two months past his 17th birthday. Pte Stephens had already been wounded on two occasions (shell wound, Flers, November 1916; shell wound, Le Sars, March 1917) and was recovering back in England when he along with his best mate Pte Charles Samways (photograph left, sitting) went Absent Without Leave for six weeks during September and October 1917 and were classed as illegal absentees. They were apprehended, but despite the lengthy time AWOL which would normally have led to a FGCM, both were returned to their unit in Belgium at the end of 1917. Pte Stephens would be wounded a third (gunshot wound, Dernancourt, April 1918) and fourth time (gassed, Morlancourt, June 1918) and then on the 4th October 1918, the very last day of fighting by the 22nd Battalion, he answered the call for volunteer stretcher bearers and for his conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty was awarded the Military Medal. After the withdrawal of the Australian troops from the front, Pte Stephens and Pte Samways were issued with passes for English leave, but on the 11th November 1918 – Armistice Day – they both went AWOL again, this time for three weeks, which landed them Field General Courts Martial and 40 days Field Punishment Number 2.

Like Pte McFarlane, Pte George Stephens (photograph left, standing) came from Port Melbourne and upon enlisting was learning a trade as a labourer with Taylor Pipe Works. His service record states an age of 18, but when Pte Stephens enlisted in July 1915 he was only two months past his 17th birthday. Pte Stephens had already been wounded on two occasions (shell wound, Flers, November 1916; shell wound, Le Sars, March 1917) and was recovering back in England when he along with his best mate Pte Charles Samways (photograph left, sitting) went Absent Without Leave for six weeks during September and October 1917 and were classed as illegal absentees. They were apprehended, but despite the lengthy time AWOL which would normally have led to a FGCM, both were returned to their unit in Belgium at the end of 1917. Pte Stephens would be wounded a third (gunshot wound, Dernancourt, April 1918) and fourth time (gassed, Morlancourt, June 1918) and then on the 4th October 1918, the very last day of fighting by the 22nd Battalion, he answered the call for volunteer stretcher bearers and for his conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty was awarded the Military Medal. After the withdrawal of the Australian troops from the front, Pte Stephens and Pte Samways were issued with passes for English leave, but on the 11th November 1918 – Armistice Day – they both went AWOL again, this time for three weeks, which landed them Field General Courts Martial and 40 days Field Punishment Number 2.

Pte Oswald Hunt (photograph left, front centre) was a 22 year-old labourer from Richmond when he enlisted in July 1915 and from his service records appears to have been ever present with the 22nd Battalion on the Western Front up to October 1917, including Pozieres, the Somme during the harsh winter of 1916/17, Bullecourt and 3rd Ypres. In February 1917, after the battalion was resting in Shelter Wood having been relieved from front line duties, Pte Hunt went AWOL for one night which earned him 120 hours Field Punishment Number 2 and forfeiture of 7 days pay. During the attack at Broodseinde on 4th October 1917 Pte Hunt was wounded in action and then transferred back to England for recovery. It was in December 1917 that Pte Hunt went AWOL from Command Depot Number 3 at Hurdcott, and it was not until almost two months later that he was arrested in Manchester as an illegal absentee. The subsequent District Court Martial found Pte Hunt guilty and he was given four months detention and the forfeiture of 150 days pay. After the sentence was served Pte Hunt returned to the battalion towards the end of May 1918, fighting with the 22nd Battalion through to the end of their war at Beaurevoir. However with the 22nd Battalion returning to the rear for well earned rest Pte Hunt was one of four, including battalion commander Lt-Col Wiltshire, that remained to assist the newly arrived American 117th Infantry Regiment. Pte Hunt’s role was to assist a Company to the Jumping-Off Tape, but the ensuing chaos caused by heavy shell fire meant that Pte Hunt had to take leadership to the JOT, and then during the subsequent attack he noticed that one section became held up. Pte Hunt went forward, took control and with several men worked round and neutralised the enemy post. For his coolness, determination, and in showing leadership to untrained men Pte Hunt was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal. Given the date of 7th October 1918, this selfless act of initiative and bravery was probably one of the last actions performed by an Australian infantryman during the war.

Pte Oswald Hunt (photograph left, front centre) was a 22 year-old labourer from Richmond when he enlisted in July 1915 and from his service records appears to have been ever present with the 22nd Battalion on the Western Front up to October 1917, including Pozieres, the Somme during the harsh winter of 1916/17, Bullecourt and 3rd Ypres. In February 1917, after the battalion was resting in Shelter Wood having been relieved from front line duties, Pte Hunt went AWOL for one night which earned him 120 hours Field Punishment Number 2 and forfeiture of 7 days pay. During the attack at Broodseinde on 4th October 1917 Pte Hunt was wounded in action and then transferred back to England for recovery. It was in December 1917 that Pte Hunt went AWOL from Command Depot Number 3 at Hurdcott, and it was not until almost two months later that he was arrested in Manchester as an illegal absentee. The subsequent District Court Martial found Pte Hunt guilty and he was given four months detention and the forfeiture of 150 days pay. After the sentence was served Pte Hunt returned to the battalion towards the end of May 1918, fighting with the 22nd Battalion through to the end of their war at Beaurevoir. However with the 22nd Battalion returning to the rear for well earned rest Pte Hunt was one of four, including battalion commander Lt-Col Wiltshire, that remained to assist the newly arrived American 117th Infantry Regiment. Pte Hunt’s role was to assist a Company to the Jumping-Off Tape, but the ensuing chaos caused by heavy shell fire meant that Pte Hunt had to take leadership to the JOT, and then during the subsequent attack he noticed that one section became held up. Pte Hunt went forward, took control and with several men worked round and neutralised the enemy post. For his coolness, determination, and in showing leadership to untrained men Pte Hunt was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal. Given the date of 7th October 1918, this selfless act of initiative and bravery was probably one of the last actions performed by an Australian infantryman during the war.

The effectiveness of discipline and punishment

Military discipline is ultimately designed to prepare men for the traumas of battle and for them to remain as an effective and cohesive unit during the heat of the battle. Furthermore, the British had developed over centuries the ability to turn working men and those from the bottom rung of society into effective soldiers to successfully achieve its political and economic goals creating one of the world’s greatest Empires of the time. As a result British military discipline was one of the strictest within the armies that fought in the First World War. This included the use of the death penalty which saw the execution of 346 men for military offences during the war. To help judge whether this strict rule of discipline, to which Australian politicians, public and servicemen were broadly against, was necessary it needs to be placed into the context with what was happening elsewhere. For example within the German Army, the death penalty was used sparingly with only 48 out of the 150 death sentences carried out. However, desertion to the enemy was common, happening almost daily on the Somme in 1916, but was very rare for the British and almost unknown for the Australians. The rigidity of the British disciplinary code was envied by General von Ludendorff, who in his memoirs stated that the absence of a British-style military discipline was a significant factor in Germany’s defeat.

The numbers of convicted French soldiers shot are unknown due to some summary executions, but in the region of 600 were carried out from 2,000 condemned men that are documented. Although a higher number than in the British Army, this punishment did not stop the potentially devastating French Army Mutinies of 1917, which was caused by low morale at that time. Other armies, such as the Italian were more punitive. In Italy, the ancient Roman practice of decimation, choosing and then executing soldiers by lots from a unit that had failed was reintroduced when a unit had mutinied in 1916. No nation shot more of its own than Italy during the First World War, but its poor performance was more down to incompetent leadership, poor training, low morale and inferior equipment. As for Russia, flogging was reintroduced in 1915 but discipline broke down completely leading to a full scale revolution in 1917.

For the British the strict disciplinary code that was used by the British Army and its Dominion forces provided the foundation for ultimate military success, and furthermore the British Army remained the only army on the Western Front not to experience serious military problems on the front-line. However, as can be seen from the above military success is not guaranteed by just strict discipline and many other factors come into play such as leadership, training, camaraderie and morale.

It was to these other factors that the Australian people put their faith that their officers and men serving under them possessed the initiative, courage and skill to get the job done, and not encumbered by excessive threats of punishment. Frustrations often ran high within the senior British Army High Command with regard to the Australian problem of discipline, but the Australian Parliament and its senior Commanding Officers, notably Generals Birdwood and Monash stuck to the belief in their men, and they and the French people were repaid as witnessed by the events of the spring and summer of 1918 with the AIF being pivotal in the defeat of the German Army and the Central Powers.

Did poor discipline effect the fighting capability of the AIF?

Despite early failures and heavy losses particularly at the beginning of the war (Gallipoli 1915; Fromelles 1916; Pozieres 1916; Bullecourt 1917) and a distrust of British High Command, the AIF developed into one of the most revered fighting forces of WW1. The tide of fortune appeared to change with the well planned and well executed attack by General Plumer’s British Second Army at Messines in July 1917 with the 3rd & 4th Australian Divisions attacking with the New Zealand Division on the right flank of the attack. However the effectiveness of the AIF grew when fighting alongside fellow countrymen, firstly the 1st, 2nd & 3rd Divisions at Broodseinde on the 4th October 1917 – ‘greatest victory since the Marne’ (Plumer) – and then as the Australian Corps from June 1918 onwards.

The Australians really came to the fore in 1918, firstly with the dogged defence against the German Spring Offensive from Hebuterne to Villers-Bretonneux after Ludendorff’s storm-troopers had swept over the old Somme 1916 battlefields towards Amiens. Then when all was relatively quiet on the British sector in late spring and early summer 1918, the Australians kept the pressure on the German Army with their series of small but successful ‘peaceful penetration’ raids which had a demoralising impact on an exhausted enemy. After Monash’s successful Hamel attack on 4th July 1918 in which the principles of integrated warfare were superbly executed, the Australian Corps along with Currie’s fresh Canadian Corps were selected by the Allied Supreme Commander General Foch to spearhead the breakout from Amiens, the result of which on the 8th August became known as the ‘black day for the German Army’ and was the start of the final 100 days leading to the ultimate Allied victory and the Armistice.

However this critical success on the battlefield was happening at the very time that the strain on the Australian fighting units in terms of manpower and the stress on the individual soldier was at its greatest. For some the breaking point had been reached leading to an increase in indiscipline within the AIF as the war progressed, but overall the morale of the men remained high and their determination to see this through remained resolute.

The gratitude and respect of the French is encapsulated in the words of M. Georges Clemenceau, Premier of France when visiting the Australian front on the 7th July 1918 after the Battle of Hamel (photograph right). “When the Australians came to France, the French people expected a great deal of you… We knew that you would fight a real fight, but we did not know that from the very beginning you would astonish the whole continent… I shall go back tomorrow and say to my countrymen, I have seen the Australians, I have looked in their faces, I know that these men will fight alongside of us again until the cause for which we are all fighting is safe for us and for our children.”

The gratitude and respect of the French is encapsulated in the words of M. Georges Clemenceau, Premier of France when visiting the Australian front on the 7th July 1918 after the Battle of Hamel (photograph right). “When the Australians came to France, the French people expected a great deal of you… We knew that you would fight a real fight, but we did not know that from the very beginning you would astonish the whole continent… I shall go back tomorrow and say to my countrymen, I have seen the Australians, I have looked in their faces, I know that these men will fight alongside of us again until the cause for which we are all fighting is safe for us and for our children.”

Conclusion

This case study using the service records of the 154 infantrymen of the Australian 5th/22nd has illustrated the poor discipline of the Australian soldier in the First World War, as shown by the high level of Courts Martial and absenteeism in general, and that this problem was exacerbated by the conscious choice by the Australian Parliament and courts in which punishments to use during this time. In addition, with the exception of a tiny minority of bad characters that according to Bean had made their way into the AIF, the vast majority of the men with poor discipline records were indeed regular ‘Diggers’ that did their time at the front, became casualties, awarded for bravery, and promoted at the same rate as their mates that had kept out of trouble. The character of the Australian soldier suggests that they were more likely to be pre-disposed to pushing the limits of discipline, however they were able to do this knowing that they were safe from the death penalty, and that the two main punishments of humiliation which they detested, namely being returned to Australia in disgrace and Field Punishment No.1, were not being used. Furthermore the study of this cohort that were one of the first and last Australian units on the Western Front has enabled us to illustrate that discipline in the AIF did get worse as the war progressed, a sign that battle fatigue and stress did indeed play a part.

Looser discipline was considered by many of their superior officers as an acceptable ‘price’ when put beside their performance on the battlefield. Australians and New Zealanders were known as among the most fearsome and willing troops of the Allied forces. Overt discipline was therefore, and probably uniquely, less of a necessity for the Australians than soldiers from other countries as the senior command trusted that the character of the officers and men charged with carrying out the orders would see it through. By the end of the war Field Marshal Douglas Haig conceded that Australian battle discipline had held up during the war despite the poor discipline away from the front. As Lieutenant-General Monash (photograph right) later wrote:

Looser discipline was considered by many of their superior officers as an acceptable ‘price’ when put beside their performance on the battlefield. Australians and New Zealanders were known as among the most fearsome and willing troops of the Allied forces. Overt discipline was therefore, and probably uniquely, less of a necessity for the Australians than soldiers from other countries as the senior command trusted that the character of the officers and men charged with carrying out the orders would see it through. By the end of the war Field Marshal Douglas Haig conceded that Australian battle discipline had held up during the war despite the poor discipline away from the front. As Lieutenant-General Monash (photograph right) later wrote:

“Very much and very stupid comment has been made upon the discipline of the Australian soldier. That was because the very conception and purpose of discipline have been misunderstood. It is, after all, only a means to an end, and that end is the power to secure coordinated action among a large number of individuals for the achievement of a definite purpose. It does not mean lip service, nor obsequious homage to superiors, nor servile observance of forms and customs, nor a suppression of individuality… the Australian Army is a proof that individualism is the best and not the worst foundation upon which to build up collective discipline”.

References and Reading Material

Service Records held by the National Archives of Australia

Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-18. Vols I & III – The Story of Anzac; C.E.W. Bean

Crime and punishment on the Western Front: the AIF and British Army Discipline – thesis by EJ Garstang, Murdoch University,2009

FIRST WORLD WAR TIMELINE

FIRST WORLD WAR TIMELINE